I take my shoes off and walk into my Bustan in the Netherlands to check on the plants. I feel my grandfather Abdallah walking with me in Bustan Rieha several decades ago. I look at my fingers and see my grandmother foraging huweyrneh by the stream. Their blood flows into my veins, guiding my hands that seem to know what I have never learnt.

Bustan: البستان

A garden, grove, orchard. It could be any of these things. Large or small. A piece of land, attached to one’s house or further away, that one cares for, cultivates, and eats from. A bustan is the staple of a Fallah.

A fallah might farm as a ‘profession’ but he might not. He may own land or rent it or just live on it and use it. He might be a building contractor and underground Ghorani rebel, or a university professor. But he’ll always have a bustan (or at least a few plant pots when he’s displaced.) Without a bustan, a fallah is destined to a life of eternal yearning and deteriorating health.Huweyrneh: حويرنة

O… Just the name makes my mouth water.

Sow-thistle-ish: A wild edible/medicinal plant. Bitter. The secret is in preparation. After plucking (in season), washing and chopping, you rub it with salt till it wilts and its water drains out (but not too much salt or it would lose its edge) - finally shaping it into a little ball in your palm. My aunts would then place the little ball in a small plastic bag and send it to us with whoever was crossing the border to Jordan. We mixed it with yoghurt, drizzled it with olive oil, and scooped it up with a piece bread to its final destination (I’m seriously drooling at this point.)

رجعت لأصلها، فلاحة

She went back to her roots, a Fallaha

Fallahin (plural): A term lost in translation. In English and Dutch, it’s ‘farmers’ - eliciting images of cowboy hats and horses, or boeren wearing wooden clogs collecting cow manure. ‘Peasants’ is another translation, carrying the stamp of poverty and ignorance fabricated by medieval European landlords and exported to the rest of the world. But ‘Fallahin’ is much more than any of these things.

الفلاحين Fallahin

Fallah/a (singular): one who ploughs the land, cultivates, plants and forages. Village dweller.

Filaha = Husbandry: the care, cultivation and breeding of crops and animals. The management and conservation of resources. Not a haphazard practice, but studied and developed, passed down from one generation to the next (compiled in kutub al-filaha that are often disregarded by the Anglo-Saxons.)Falh (root): Winning, staying in goodness/abundance, achieving what one desires.

Al-Falaah: Salvation (as used in al-adhaan- the call to prayer)

Fallahi: of the fallahin, in the Fallahi ways (also, the fallahi accent.)

Fallahi has come to mean crass, tasteless, kitsch, uncultured, uneducated. Similar to the word Philistines, which originally referred to the pagan natives of the holy land, the term devolved to mean uncultured, vulgar, uncivilised- and god save us - uncircumcised. Thanks to Judaism and then Islam, circumcision became a common practice amongst the once-philistines later Fallahin. They call it Tuhur and would gladly tell you about it. They do not shy away from describing bodily parts, functions or practices as do the city folk. Gender segregation was not part of their reality until religion assumed a conservative garb and weaselled itself into their homes. But their spirit has not been totally subdued. The Fallahin still laugh without restraint, clapping and singing at any possible occasion. Who else would sing for sage?

[The film/post here offers a glimpse.)

The Fallahin marry young and have many children (but some don’t.) They help each other during harvests, they barter and they forage. They breastfeed each other’s babies who thus become milk brothers and sisters, forming new bonds to an extended family. (I should say, did. The Fallahin have less kids nowadays and no one breastfeeds someone else’s babies anymore. We now have baby formula - clearly superior to breastmilk. The Fallahin still help each other however.)

Even when consumerism crept in, the Fallahin maintained a simple life. One dishdasheh for work-perhaps two, and a dishdasheh for special occasions (usually one’s intricately embroidered wedding gown) and something to sleep in (could simply be the under-dress). A woman wore her dowry on her wrists or around her neck, gifting it to loved ones before she died. Most of the possessions of the Fallahin they made themselves. They fashioned their shibabehs from reed and played music by water springs. If I had to sum it up, I’d say that

Al-fallah is someone who appreciates a ripe lemon more than he would a pearl.

The Fallahin are thus clearly a dangerous people. They have a direct relationship with their food source, with plants, animals, and nature at large.

FOOD SOVEREIGNTY1

is the basis of freedom, Thus everything in our modern world is trying to obliterate it, brainwashing us into desiring luxury and convenience, turning us into enslaved consumers, terrified of dirt and addicted to anti-bacterial soap. The tactics are working. When I excitedly told one of my Palestinian relatives about my vegetable garden, she expressed alarm. ‘Be careful,’ she said, ‘you don’t want to exert yourself.’

Did you forget where we came from, woman?

Once a Fallah, always a Fallah

My father’s family came from Silwan, just outside the walls of old Jerusalem. Fallahin 100%. But while Silwan began as a farming village, it has been reduced to a densely populated town with nothing but stones and an ever growing number of confiscated homes with big TV’s. Most of my father’s siblings morphed into (educated and employed) city dwellers, but they remained simple in their ways and often kept a garden. They delighted in nature, grabbing any chance they got to plant or forage. My father could hardly walk on his stick when he last visited my Dutch Bustan, but he could not resist pruning the trees. He said it reminded him of Bustan Rieha.

Rieha al-maliha: Jericho the good.

That’s how my father’s family called it. When I was a child, we used to go to Rieha every winter, crossing the Allenby border, getting strip searched, interrogated, intimidated and insulted. Once we’d arrive at the family Bustan however, all negative border-residue would immediately be erased.

Rieha was my paradise, it was the land of freedom in contrast to our rule-laden house in Amman. It was there that I first tasted life as a Fallaha. But things have changed. As far as I know, of all my father’s still-living direct family members, ‘Ami (dad’s youngest brother) and I are the only two who cultivate anything. The rest are uninterested, too busy or even burdened by the few trees in their bustaan. ‘There’s no one to collect the dates and they fall on the ground and rot, making everything filthy.’ But at least, Rieha’s Bustan is still there, and ‘Ami is taking care of it.

In Rieha at large, agricultural land has been transformed into imposing villas with high walls, swimming pools and no gardens, which members of the PLO built with the aid money they gathered for the Palestinian cause. Some PA officials even take land without paying the owners, just like their employer-the great occupier. The little agricultural land that has remained is dry. Israel controls at least 80% of the water, and it’s stingy with what it allows in2. Those tending the land have done their own share of soil destruction, buying into the false promise of chemical solutions to agriculture.

The last time I was in Rieha, I asked my uncle to take me to visit the family bee hives. We found only a rubble of broken hives, moth-eaten combs and a decrepit beekeeper. A few days earlier, I had visited the hives of an Israeli beekeeper in an occupied hillside on the outskirts of Jerusalem. His bees were thriving. We bonded over natural beekeeping and promoting peace. Once I mentioned the IDF raids on Jenin however, he disappeared. When I contacted him afterwards, he acted like he did not know me.

Once were Fallahin*

Before the British mandate, three quarters of the Palestinian population lived in rural areas and relied on the land for their sustenance. Most of the Palestinians were thus Fallahin. They also cultivated most of their wheat, but then came the ‘improved-imported and eventually genetically modified.) Since the birth of Israel, more than 350 Palestinian villages have been destroyed. The Fallahin started to go extinct. The ones that remained continue to suffer under the occupation: Rationed water, land annexation and assaults during harvest seasons. They have also been prohibited from foraging3. Many Fallahin have been forced to quit. But not all is lost. Some Fallahin have remained, and there is a growing movement in the diaspora amongst peers reclaiming their Fallahi roots, preserving the seeds and the songs.

The crime of foraging:

Wild za’tar (Syrian Oregano), sage, ‘akoub and other weeds that have sustained the Palestinians for decades have been placed by Israel on the ‘protected plants list.’ Foraging is thus punishable by law. This is done purely for the purpose of ‘nature conservation.’ It has nothing to do with depriving Palestinians – most of whom live under the poverty line - of the little resources they have. Luckily Israeli farmers developed domesticated varieties of plants, as in the case of Za’tar, and sold it to the Palestinians, thus filling the gap. (here’s a good source, albeit not to be cited.)

Nature conservation and innovation:

While the Fallahin continue to steal wild plants and destroy the environment with their small Basateen, Israel leads in nature conservation and bomb-dropping (the latter serves to control population increase. Gaza was really too crowded.) Think of all the pine forests they planted replacing Palestinian villages. The latest fire that broke outside Jerusalem on the Day of Independence was likely invigorated by the highly flammable pine4 (though divine intervention might be at play for those who still believe.) As you might know, ash is a good source of natural potassium and other source elements that could be beneficial for the soil. Furthermore,

Israel tops the western world in their use of Pesticides

They’re also kind enough to include the Palestinians in their campaign, and not just any Palestinians… Gazans! Israel sprays more than 40 kilometres against the Gaza security fence with beneficial chemicals like Oxygal and Glyphosate (the active ingredient in RoundUp.) The droplets reach 1,200 meters into Gaza – infiltrating the crops – affecting leafy greens especially (source).

//I should probably use the past tense here, as I doubt they’re currently still spraying - but maybe they’re making up for it by including beneficial chemicals in the bombs.//

They used to spray twice a year, depleting thousands of dunums of agricultural land in Gaza, and all this without asking the Gazans to pay! <Did I type ‘depleting’? Dam auto-correct!>

Not only is Israel a leader in pesticide consumption, it is the 9th largest exporter of Pesticides globally. There is no denial that science and technology are some of Israel’s great achievements: from medicine, agriculture, security, and information technology. In fact, Israel is listed as the 10th most powerful country in the world (source).

Now, some have claimed – to no real evidence - that pesticides are detrimental to the environment and even to human health. Some say it’s actually pesticides that have caused the alarming increase in human-cancer and bee-deaths. I don’t usually entertain such conspiracy theories, but assuming this is true and it’s bye-bye bees:

Do not fear. Israeli companies come to the rescue.

Bee Robotics

Take Edete Precision pollination for example, it provides machines that ‘give nature a helping hand,’ by providing ‘genetically compatible, high-viability pollen, tested for fertility and specifically matched to your trees.’ When I first heard about them, they were targeting almond trees, now it seems they’re focused on pistachio (much to be said about pistachio!) I’m sure they’re developing their machine for other kinds of props as we speak.

Then there’s Arruga AI Farming, another Israeli company that provides autonomous robots that replicate the work of bumble bees in greenhouses, thus eliminating the complications of wild pollination. Not only that, these automated robots also fill the gap of the ongoing labor crisis. Who needs employees when you have machines!

Another Israeli bee-invention that is worth mentioning, comes from a company called ‘BeeWise: saving bees to feed the world.’ Given the problem of bee-hive collapse (currently at 40%+ per year) the company has created solar-powered self-sustained and regulated bee hives, which they call a BeeHomeTM (natural bee-dwellings inside trees, in baskets of straw or clay or wood are so overrated. Give me hard-plastic baby!) With full remote monitoring, (sugar) feeding, and treating varroa mites (with chemicals) beekeeper can check their hives from the luxury of their homes using their phones. No need for the messy business of interacting with these nasty insects whose primary purpose is to pollinate food for our consumption and provide honey to sweeten our tea.

I have to say that Israel is not the only one working on such wonderful inventions. Dutch scientists have also been busy, they say they can create swarms of bee-like drones to take over in case of an insect apocalypse (source). MIT has recently developed a Robot Bee that can do the work of a real bee. Birds or dragonflies can’t eat robot bees – but who cares, those will die off too and we’ll make robot birds that sing on demand. But maybe we don’t need to get there and real bees will be saved - given the development of anti-mite RNA treatment for beehives that uses a similar technology to Pfizer’s Covid vaccine. Given the swooping success of the Covid experiment, we should be set at ease. But if this too fails, it’s good to keep something up our sleeves.

This is all reassuring.

There will be no need for bees in the future and no need for Fallahin. No reason to mourn their extinction.

If you’ve ever burdened yourself with caring for a plant and saw it growing; if you’ve ever seen a rainworm do a pirouette in compost, or two ladybugs mating, you’d know that there’s nothing special about these things. There is nothing magical or spiritual about the dance of the bee, or how the flower opens up to receive it as a lover would meet the lips of their beloved. Just like there’s nothing special about sun-rays, except for causing skin cancer. We can get a better tan in a tanning salon, we can grow plants under LED lights, and there are pills for Vitamin D. In fact, the sun itself is unnecessary. Just use Lenor laundry softener and ‘je hebt geen zon nodig.’ You don’t need the sun.

So… we can happily continue to destroy the natural world, and instead of wasting our energy, money and brilliant minds on restoring the earth, fauna and flora, we can develop more efficient robots that mimic nature. We’ll need a lot of batteries, but luckily there’s still some Amazon rain forest left, not to mention Indonesia, The Congo, Ukraine, Alaska and many other spots with a good surplus of raw materials. We only need to cut down some trees, instigate a few civil wars and dispose of a few human beings. But as Gaza has taught us, human life is cheap and we all have the right to ride electric.

Welcome to the future, folks. I’ll lag behind here, thank you, in the present- perhaps already the past, and take my bare-feet to the bees.

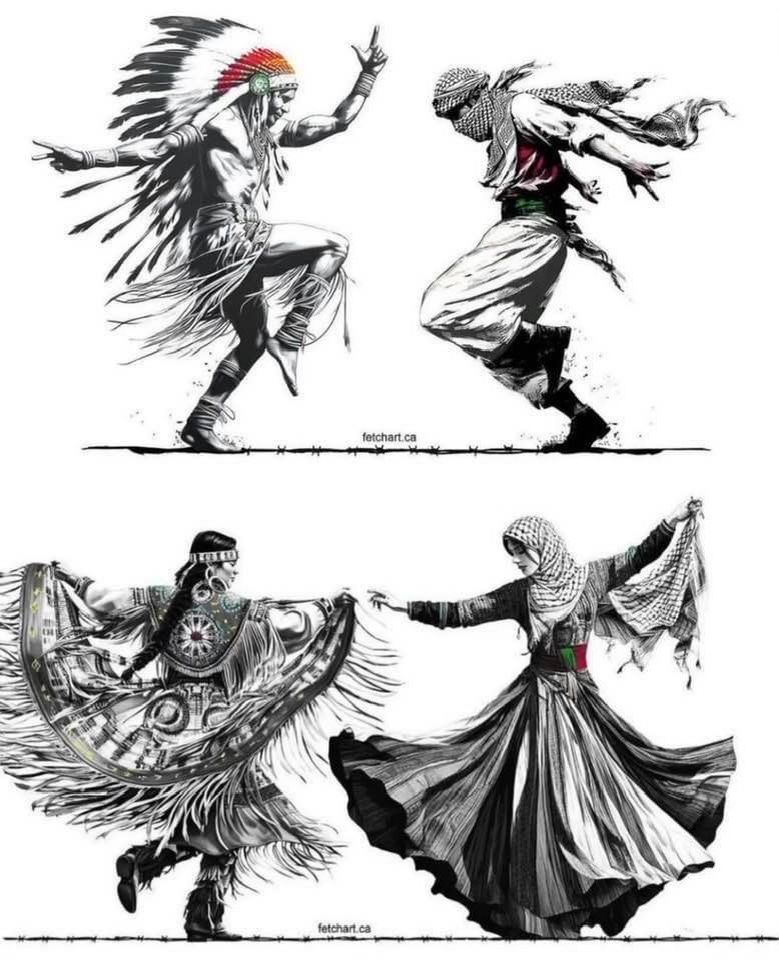

The title Once Were Fallahin is inspired by the film Once Were Warriors, which tells the story of a Maori family struggling with alcoholism, poverty and domestic violence. The aboriginals of New Zealand and Australia, the indigenous of the Americas and other native peoples have all suffered a similar fate as the Fallahin and Palestinians.

By artist Christina Damianos

No one speaks about food sovereignty better than Vandana Shiva. A woman with passion and courage who stood up against Monsanto and inspired the seed preservation movement. If I would chose a role model, she would be it. There’s a lot on-lineabout her work, here’s one:

An excellent infographic on Israel’s restrictions on Palestinian food sovereignty can be found here: https://visualizingpalestine.org/visual/food-sovereignty/

Perspective on the fire of independence day: https://www.palestinechronicle.com/largest-wildfires-in-israels-history-everything-you-need-to-know/

Lana, this essay touches the sadness just below what I keep away. Yet calmer I become in finally touching that sadness.

My mother sent me a letter regarding her days on our farm during harvest as a child. How the migrant hands ate dinner sitting on the lawn, how the meals were prepared and how the women cooked all day, how they smoked the hams ahead of time, how the vegetables and fruits came from the garden, the orchard, how lemonade was taken to the fields for the workers, workers who would lie down and nap on the lawn after lunch. How her grandfather took her places, like where the sorghum was made, and where the mushrooms grew, and where his buggy and horses were kept.

Later, a highway was run through the middle of the farm, right of domain, right between the house and the barns. Separations continued. Tractors replaced the horses and workers. Extended families became nuclear families as children moved into the cities. As a child I watched the crops being harvested and the men filling up bins in the barns and silos with seed, and asked why they didn't sell all the harvest? Great uncle Gaylen said they needed the seed to plant the next year. I returned years later, and asked why they didn't keep the seed anymore? Gaylen said it wasn't allowed. One had to buy seed now new every year. Further separations. Later the interstates took the traffic away from the road through the farm, but it was of no consequence, the orchards had dried, the animals had gone to market, small farms were sold, and were now just big farms owned by corporations. Grandmother moved to Colorado, and had the largest garden in the neighborhood. "You have to get the roots out, or the weeds come back," she instructed me. The roots were all out now from the farm, and no-one was coming back. Over a hundred miles of corn, the only moving animal is a mechanical elephant, combining all the past into one giant machine.

the link for #2 isn't linking